Campo Santo / Jérôme Combier

Project

Whoever makes the soup must eat it.

Auguste Blanqui

Campo Santo, which takes its name from the book by W.G. Sebald, is about the exploration of a forgotten place, Pyramiden, formerly the flower of Soviet culture and most northerly city in the world. It is situated way up in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard (Spiztberg) and was once, during the golden age of western and more pertinently Soviet socialist industrialisation, a successful model of how human organisation can be centred around work. Today, the abandoned city is synonymous with indisputable destruction, whose cause is primarily linked to economic decline and most likely the bankruptcy of communism and a particular cultural model. Campo Santo is also a journey through the wreckage and a look back on the special place that is Pyramiden, a mining town situated in the Arctic Circle, on the 78th parallel.

In this case, Campo Santo is both a concert and an audio-visual installation whose material is taken from the source, from the site of Pyramiden itself, a world weary guardian of a collective memory. Campo Santo places itself at the meeting point of music, visual arts, literature, cinema, and dance. Above all, it is an object of art. The thinking behind its conception and construction (readings of Charles Fourier, Robert Owen, Auguste Blanqui, Vaneigem, Derrida), remain in place like a kind of underground architecture, furtively emerging during a sentence or a paragraph. These texts are the building blocks of Campo Santo, which unfolds in the form of tableaux: the community, abandonment, decomposition, hauntology...

Campo Santo is also a reflection on Marxism and Marxist criticism, on the Utopia that Pyramiden could have been within the Soviet sphere. On this point, the project draws from Jacques Derrida’s book, Spectres of Marx.

Campo Santo brings together the following artistic team:

Jérôme Combier (composer)

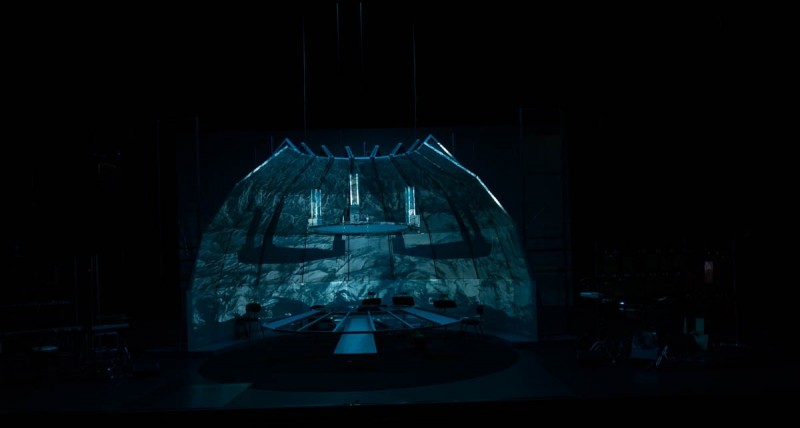

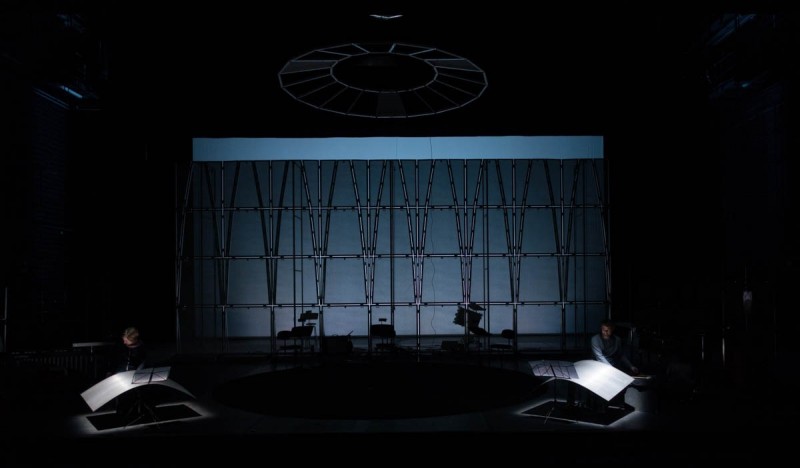

Pierre Nouvel (stage design, video artist)

Bertrand Couderc (lighting design)

Robin Meier (digital music programmer, plastic artist)

Alban Richard (choreographer)

Sébastien Naves (sound engineer)

Thomas Leblanc (stage manager)

the musicians of the Cairn Ensemble :

2 percussions

1 flute

1 electric guitar

1 accordion

Through the exploration of an empty space, through the replica model of Pyramiden, a thought process takes shape about economic and social utopias — Pyramiden reminds us of the phalansteries of northern France — and about the models of human organisation based on notions of labour and productivity, and the search for a collective memory. Most of all, Campo Santo moves towards a search for epiphany of deserted human places.

"When the dead return, it’s not in the form of a resurrection, or as a lively, happy, and fertile presence, which opens to the future and future books to be written. In any case the dead don’t return; they have always been there. But they don’t pretend to be present in the same way as living people. They are present as dead people: like rustling shadows, unintelligible wailing, like ‘the traces left behind by past suffering and which show themselves (…) in the form of uncountable lines crossing history,’ and of course like the grey nebula, the mixed black and white of photographs."[1]

[1] Gwenaëlle Aubry, Le Page blanc (The Blank Page), P. 310, in Face à Sebald, éditions Inculte, Paris, November 2011

Programme

Campo Santo is a ghost story, and it will be the domain of electronic means to reincarnate “those voices dear to us which have fallen silent”: virtual choir, spectral ballet, literary fragments, and traditional songs. “Hauntological” material will be at the heart of the artistic process. Structured around the themes of (economic) destruction, decomposition, re-working of time, voice, and the collective body, Campo Santo is also an attempt to gain perspective on writings from 19th century economic utopias: that of Charles Fourier, who contributed the to phalansteries experiment in northern France, of Robert Owen, who put together a cooperative movement centred around the cotton mills in the Scottish village of New Lanark, founded in 1874, as well the ground-breaking socialist writings of Auguste Blanqui. In 1834 he wrote, “Whoever makes the soup must eat it.”

Wealth is born from intelligence and labour, humanity’s heart and soul. But these two forces can only act with the help of a third, passive element, the land, which they put to work through their combined efforts. It thus seems that this indispensable instrument should belong to all men. Such is not the case. [1]

Form

Campo Santo immerses the audience into a changing space, like into the centre of a city or other place. In this sense, Campo Santo needs an open-ended installation. The work evolves in the form of revolving tableaux which follow each other without being announced. Each of them leads to a possibility of reflection, always through a dream-like prism and in the context of a promenade, in the spirit of Sebald.

Tableau 1: order and beauty

Tableau 2: re-working time / accelerated disintegration

Tableau 3: the collective body (ballet and virtual choir)

Tableau 4 : epiphany of forgotten places: in this tableaux, micaceous black sand will fall from several overhead locations onto the stage (controlled by MIDI), impacting sensitive metallic surfaces, creating sounds that will be amplified and electronically modified.

Tableau 5 : Eternity through the stars

Pyramiden

Pyramiden is a workers city built during Soviet times and located in the far north of Norway, just 10 degrees from the North Pole, on the archipelago of Svalbard. It takes its name from the pyramid-shaped mountain it was established at the foot of, by Sweden in 1910. In 1926 it was sold to the USSR who then leased it to the state mining company Arktikugol in 1931. The community was completely autonomous and was managed like a huge company of nearly 1500 employees until the late 1990s.

There was mo money in Pyramiden and the community raised livestock and grew produce in greenhouses that the central government brought from the continent. In the 1960s, Pyramiden miners produced around 200,000 tonnes of coal per year, and 248,000 tonnes for the year 1978 alone. After the fall of the Soviet Union, production gradually decreased, and by November 1996 there were only 590 inhabitants remaining: 467 men, 120 women, and 3 children. In the spring of 1997, although the swimming pool and hotel were renovated, the production figures were only 20,000 tonnes per year. On March 31st 1998 the mining operation ceased. The Anna Akhmatova was the last supply ship to leave Pyramiden, loaded with what the Trust Arktikougol considered important to preserve from the disused city. Library books, film reels, and records remained behind and can still be seen in place today.

"Curiously, the most perfectly communist town in the world is not located in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, but in the capitalist West, within a NATO country, Norway. This town is situated in the Arctic, on an archipelago called Spitzberg, or Svalbard, as Norwegians call it, at a latitude of 79 degrees north. Within this ideal socialist society, everything is free: the return trip there and back at the end of the contract, childcare, school, a well equipped hospital, accommodation in a four-storey building with modern heating, not to mention the food: red and black caviar, greenhouses full of fresh vegetables, and coops and pens for chickens, cattle, and pigs. (…) The mining town of Pyramiden was built as a late expression of the Russian plan and the utopian avant-garde. And that’s exactly how it looks today – only it has been abandoned: its mines are closed, and its buildings are empty." [2]

Musical Considerations

Before the writing process, the project requires proper research, including a trip to the Spitzberg archipelago, where we can record or sample series of sounds — beat-up piano, metallic sounds from cisterns, tin pots, pipes and radiators, the wind and the seagulls — and to compile still and filmed images that will be used as source material for the musical composition and the scenography.

The array of percussions mainly calls for standard metallic instruments, without bringing in keyboard percussions: bell plates, steel-drum, tam-tam, cymbals. There will also be an possibility to salvage and use metalwork material : sheet metal from copper or other metal, metal tubes and rods in brass, copper, or iron.

The electronic section has several main dramaturgical functions:

- the section itself contains scraps of dialogue in English, Norwegian, and Russian recorded during our scouting trips and will also plays back text fragments from W.G. Sebald, Auguste Blanqui, Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, and Jacques Derrida, which question the ideas from labour-related utopias.

- it brings a lyrical aspect to the piece that the percussions can’t handle. Here we might create melodic fragments, a virtual choir, a choir for all ghosts.

- it allows for sonic reconstructions: playing scores found in the school classrooms on the concert hall grand piano

Voices and singing emerge from centre stage, from an installation of suspended loudspeakers, which acts like a mausoleum of departed human voices.

Scenic Considerations

Questions for Pierre Nouvel: How to design this epiphany of locations for the stage? How to get across this feeling of a timeless space that these ruins represent? How to make an artistic representation of collective memory? How to make emerge a “hauntology” designed for the stage?

Questions for Alban Richard: is it possible to create the sensation of a virtual ballet? A ballet resembling the return of those dismissed souls who scarcely left a trace in these forgotten places? How to get across the feeling of a collective body?

"The spectre is “a strange voice, both present and non present, singular and multiple, bearer of difference, as ghost-like as a human being, different from itself and its own spirit. It is both an other and more than an other. It dislocates time. It is a trace. Although coming from the past, bringing a heritage, it is unpredictable and above all irreducible."[3]

[1] Auguste Blanqui, Qui fait la soupe doit la manger, éditions d'Ores et déjà, Paris, septembre 2012, P. 17. English translation:

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/blanqui/1834/soupe.htm

[2] Kjartan Flogstad, Pyramiden, portrait d’une utopie abandonee (Pyramiden, Portrait of an Abandoned Utopia), p. 11-12, éd. Actes Sud, Arles 2009

[3] Jacques Derrida, Spectres de Marx, éditions Galilée 1993, Paris